Dean Smith and Emily Wilson are two of my closest friends, and two of my favorite artists. They have concurrent shows on view now, across the street from each other, on Geary. Dean spends months making these meticulously hand drawn markings and squiggles on paper that eventually become something visually transcendent, topographies and landscapes beyond reference to anything specific. The expressive quality of his work is defined by an almost mechanical interaction with surface.

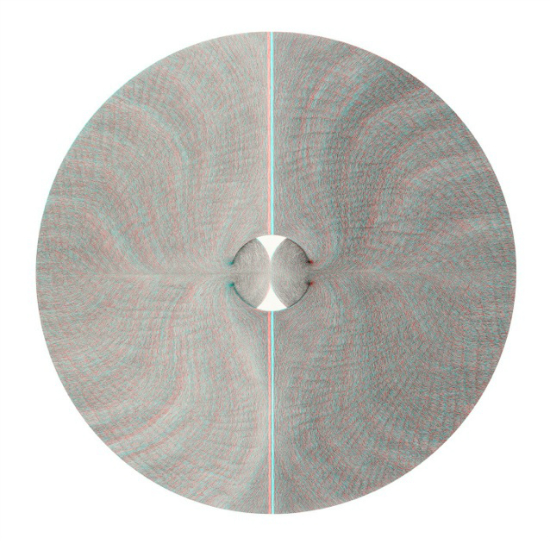

Dean’s show at Gallery Paule Anglim consists of three pieces, titled “three manifestations of anaglyphic space.” I know… but that’s Dean, be serious, he always has titles like this, he always makes us work. Each piece is reproduced from an original drawing that has been manipulated digitally to produce a three dimensional image when viewed with 3-D glasses, on hand in the gallery. One piece acts almost like a mirror, another zooms out in a rounded mound towards you, like a giant coconut but with a big “t” cut into it. You see fantastic geometric and biomorphic forms that seem convincingly of some other dimension, a dimension not only of sight, but of imagination… and at times even orifices.

Just seeing this work exhausted and disoriented me. All great work should make you sick like that. But get this, after Dean’s show, Big Chrissy and I made our way across the street to see the Adam Fuss show at Fraenkel, photograms made from animal intestines. And then a giant daguerreotype close-up of female gentle-talia! Ahhhh! Enough with the viscera! Get me to Emily’s soothing randomness!

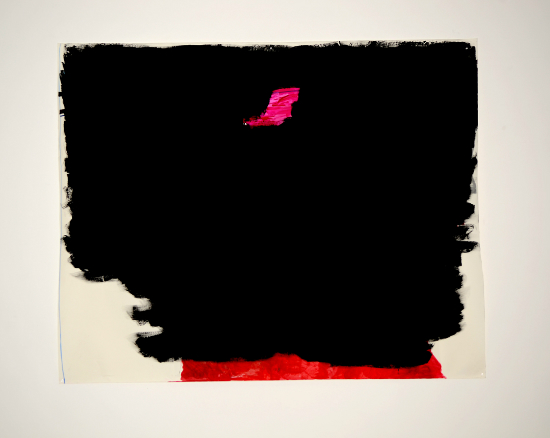

So Emily’s markings are as expressive and seemingly random as Dean’s are calculated. She also creates abstractions, but with big sloppy dripping gestures. She finds inspiration in the cinematic expressions of Antonioni and Nicholas Roeg, and I think most apparently Godard, creating wordless narratives of emotional punch. But these guys rarely crack a smile, and Emily’s obviously having fun, with color, form, paper and canvas. Visiting her studio, you experience this work as it should be viewed, stapled to the wall or crumpled on the floor, stepped on, smushed, glued to the ceiling. Thankfully, Sweetow has resisted trying to contain this work in frames. Like following Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau around Milan in La Notte as their marriage crumbles, the viewer of her work stumbles through a sort of tapestry of graphic encounters, culminating in that final confrontation when Moreau reads Mastroianni the tender love letter he wrote to her before they got married. “Who wrote that?” he asks, not remembering. With Emily, though, we don’t forget who wrote it, or the sincerity behind the expression.